今天许多灵恩派人士宣称:“大觉醒”(Great Awakening)是灵恩运动(charismatic movement)的先驱,因为二者都同出一辙、有情绪爆发的特征与敬拜投入的经历。此外,正如我们已经看到的,他们辩称这一运动是由于强调神学的精确而终止的。然而,这样的辩解,却暴露了他们一种可悲的误解,其实“大觉醒”恰是植根于强而有力的讲道和纯正教义基础上的复兴。“大觉醒”非但没有挑战正统神学,反而重建了清教徒加尔文主义的正统传承,并且(至少暂时)制止了那时代对清晰教义的严重侵蚀(此乃当时代的标志)。情感的表现始于对神话语清晰传讲的回应。

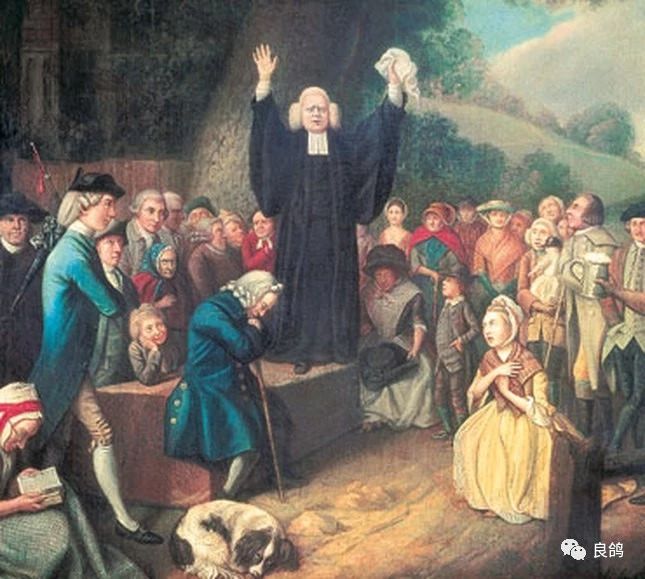

不论爱德华兹(Edwards)怀特腓(Whitefield)和那时代其他主要的传道人都因讲道的生动和直白而闻名于世。当他们用朴直的言语、活泼的形象、精确的逻辑来讲解圣经真理时,所有在圣灵主权大能之下的听众皆深受感动、大为震撼。

1741年7月8日,在康州、恩菲尔德(Enfield, Connecticut)举行的礼拜上,记载了最早的一场聚会时喊叫、晕倒和哭泣的事件。爱德华兹是当日来访的传道人,他所传讲的经文是:“他们失脚的时候,伸冤报应在我;因他们遭灾的日子近了;那要临在他们身上的必速速来到。”(申 32:35)爱德华兹那晚的讲道成了他最知名的信息:“在愤怒上帝手中之罪人”。任何读过这篇讲章的人都知道,那信息与我们这个时代“轻轻松松、无虑无忧”的精神相去甚远。

威廉斯(Steven Williams)参加了那一场聚会,在他日记中记录了当晚的情景:

我们去了恩菲尔德(Enfield),在那里遇见了来自于新港口(New Haven)亲爱的爱德华兹先生。他根据(申 32:25)传讲了一篇发人深省的信息。讲完之前,全场都不约而同地呼求、呐喊:“我当怎样行才能得救呢?”“哦,我要下地狱啦!”“我该为基督做什么呢?”等等。因此,传道人不得不半途停止,当时的哭泣和尖叫声刺透人心。等待了一段时间之后,会场安静下来,魏弟兄就做了个祷告。之后,我们从讲台下来,和人们交通,有的在这里,有的在那处,看见当晚神奇妙的大能,运行在好些人身上。哦,那些得着安慰之人,他们的面光是何等的欢愉、喜乐!愿上帝建立他们、成全他们!我们唱了首诗歌,做了祈祷,就散了会。 [1]

在“大觉醒”中,这种情绪的爆发总是发生在对所传讲信息的回应上。没有无缘无故、非理性的、纯激情的大爆发。如果有人哭泣,那是由真正的悲伤所引起的;如果有人哭泣,那反映出对神的恐惧;如果有笑声的话,那是一颗喜乐之心的表达,而不仅是空洞、没理由、歇斯底里的狂笑。

至少在狂热占领了这场运动之前,情况是这样的。

显然,从“大觉醒”到“大笑复兴”需要一步巨大的飞跃。这两个运动之间的差异非常明显,甚至连世俗的观察家也注意到了。伦敦一家报社写道:

现在的运动和18世纪大复兴截然不同。不同之处在于,后者的特点是强而有力的讲道、极度的自我厌恶和痛悔意识,无一是现代“多伦多祝福”或它产生之灵恩运动的特征。[2]英国一家基督教报纸也作出了类似的观察:

人们把这些事和怀特腓时代所看见的相比,但这一比较似乎不太合适,因为他在讲道之后才有这些现象,而这些似乎只不过是对“我们在多伦多看到的东西”的一个非常肤浅的总结。 [3]

现在,让我们对比一下威廉斯(Steven Williams)对恩菲尔德(Enfield)事件的第一手记录和这位目击者讲述的“大笑复兴”:

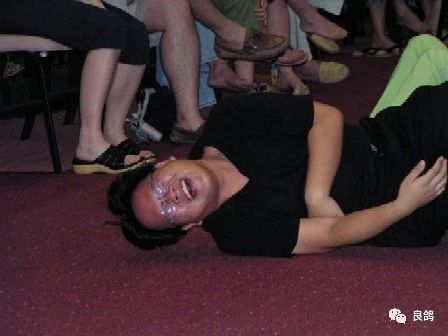

一位穿着连衣裙的女士躺在地上,似乎痛苦地扭动着、尖叫着。一个穿着深色西装,带着浓重口音的男人正站在她旁边发号施令,而另一群人则站在那里看笑话。这位女士似乎被恶魔附身了,因为她的身体以一种不自然的方式从地板上蹦下跳。那男人把她推下来,命令她“趴下”,“让它从你的肚子里出来!”另一位女士则抱着航空公司的毯子盖住她的大腿,以防她内衣走光。

这位女士连续几个分钟,起起伏伏,疯狂地尖叫。她喊着说:“亲爱的耶稣”,那男人命令她不要祷告,乃要降服于大能之下。女子把双手遮住脸,继续不由自主地大笑,男人说:“对,就是这样!你明白了!”观众们蹦蹦跳跳地鼓掌、欢呼,而那男子喊着说:“酒吧是开放的!酒吧是开放的!深深地畅饮吧!醉心于圣灵吧!” [4]

这与“在愤怒之神手中的罪人”实在大相径庭、太不一样了。如今是神被掌握在一群轻浮的暴民手中(至少暴徒是这么以为的)。这让人联想起西奈山脚下的场景,在那里,以色列人围着自己所造的神像翩翩起舞(出32)。

只要宗教运动允许情感失控,让欢快的情绪成为终极的裁判,来决定是否真是神的作为,最终就会导致这样不可避免的结果。但圣经里的神“不是叫人混乱的”(林前14:33),他的话语更不是我们宗教经验之外、可有可无的辅助。在下周结束本系列之时,我们将会慎重考虑这些重要的真理。

(改编于“鲁莽的信心”)

————————————–

God in the Hands of Giddy Sinners

by John MacArthur

Wednesday, November 14, 2018

Many charismatics today claim that the Great Awakening was a forerunner to their own movement, marked by the same emotional outbursts and experiences that dominate their worship. Moreover, as we’ve already seen, they argue that the movement was quenched by an emphasis on theological precision. But such arguments betray a woeful misunderstanding of the Great Awakening—a revival rooted in strong preaching and sound theology. Far from challenging orthodox theology, it reestablished the Puritan heritage of Calvinist orthodoxy and put a halt (at least temporarily) to the serious erosion of doctrinal clarity that was the hallmark of the age. The emotional displays began in response to the clear preaching of God’s Word.

Edwards, Whitefield, and all the other leading preachers of that era were known for the vividness and directness of their preaching. When they applied their plainness of speech, graphic imagery, and logical precision to the truths of Scripture—all under the Holy Spirit’s sovereign power—the impact on audiences was dramatic.

One of the earliest recorded incidents of congregational outcries, swooning, and weeping happened during the Sunday evening worship service at Enfield, Connecticut on July 8, 1741. Jonathan Edwards was the visiting preacher, and the text he preached from wasDeuteronomy 32:35: “Vengeance is Mine, and retribution, in due time their foot will slip; for the day of their calamity is near, and the impending things are hastening upon them.” Edwards’s sermon that night has become the message for which he is most famous: “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Anyone who has ever read the text of that sermon knows it is as far from the don’t-worry-be-happy spirit of our age as it is possible to get.

Steven Williams attended the service that night. He recorded the event in his diary:

We went over to Enfield, where we met dear Mr. Edwards of New Haven, who preached a most awakening sermon from these words—Deuteronomy 32:35. And before the sermon was done, there was a great moaning and crying out through the whole house—“What shall I do to be saved?”; “Oh, I am going to hell!”; “Oh, what shall I do for Christ?” etc. So that the minister was obliged to desist. The shrieks and cries were piercing and amazing. After some time of waiting, the congregation were still, so that a prayer was made by Mr. W. And after that we descended from the pulpit and discoursed with the people, some in one place and some in another. And amazing and astonishing the power of God was seen, and several souls were hopefully wrought upon that night. And oh, the cheerfulness and pleasantness of their countenances that received comfort. Oh that God would strengthen and confirm! We sang a hymn and prayed and dismissed the assembly. [1]

Such emotional outbursts in the Great Awakening invariably happened in response to the messages preached. There were no random or irrational eruptions of raw passion. If there was weeping, it was provoked by genuine sorrow. If there was wailing, it reflected real terror of the Lord. If there was laughter, it was the expression of a joyful heart, not just empty, spontaneous hysterics.

At least that was the case until fanaticism seized the movement.

Clearly, to move from the Great Awakening to the laughing revival requires a quantum leap. The difference between the two movements is so pronounced that even secular observers have noticed. A London newspaper wrote,

The difference between the present movement and the revivals of the 18th century is that the latter were characterised by powerful preaching, a strong sense of self-loathing and of repentance, none of which is a feature of the Toronto Blessing or the charismatic movement from which it came. [2]

A Christian newspaper in England made a similar observation:

People are likening these things to those seen in Whitefield’s day, but the comparison seems hardly fitting as his followed the preaching of the Word when these seem to follow little more than a very shallow summary of “what we saw in Toronto.” [3]

Now contrast Steven Williams’s firsthand record of the Enfield incident with this eyewitness account of the laughing revival:

A lady wearing a dress is lying down on the ground seemingly writhing in agony and screaming. A man with a thick accent in a dark suit is standing over her barking orders while a crowd of people stand all around laughing. The lady appears to be possessed by a demon because her body jumps off the floor in an unnatural way. The man pushes her back down ordering her to “stay down” and “Let it bubble out your belly!” A woman with an armful of airline blankets covers her thighs to hide the view of her undergarments.

The lady continues to flop up and down for several minutes screaming hysterically. She shouts “Dear Jesus” and the man orders her not to pray but to submit to the power. She puts her hands over her face and continues laughing uncontrollably and the man proclaims “There it is! Now you got it.” The audience jumps up and down applauding while the man shouts “The bar is open. The bar is open. Drink deeply! Get drunk on the spirit!” [4]

Surely this is a far cry from “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Now God is in the hands of a giddy mob—or so the mob thinks. It is reminiscent of the scene at the foot of Sinai where the Israelites danced around a god of their own making (Exodus 32).

And that is the inevitable result whenever a religious movement allows feelings and emotional euphoria to be the final arbiter of any legitimate move of God. But the God of Scripture “is not a God of confusion” (1 Corinthians 14:33) nor is His Word an optional supplement to our religious experience. And we’ll consider those critical truths as we conclude this series next week.

(Adapted from Reckless Faith)

微信扫一扫订阅

微信扫一扫订阅